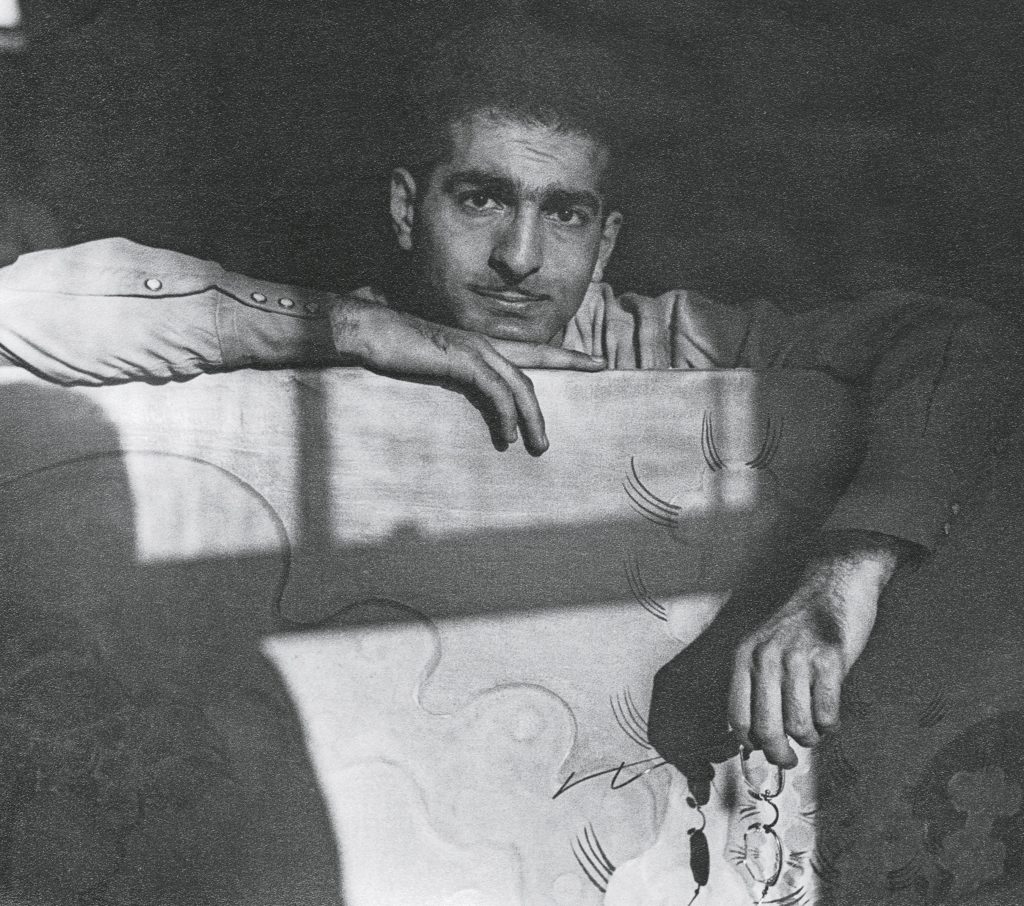

Michael Russo, author of Martin Barooshian: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Prints, 1948-1970, and I worked together to clarify and polish distinct aspects his brilliant retrospective on the artist who has been called “Pablo Picasso meets Stan Lee.” Aroian Editorial is pleased to publish Mike’s guest blog post.

What Was I Thinking?

It took me over ten years, but I finally finished my book, a catalog and biography of the artist Martin Barooshian. You see, because I have always wanted to maintain my attachment to the arts despite a career in business, I started a not-for-profit. Long before I worked with Karen — who would have saved me from myself — I named my org the descriptive but ultimately messy Society for the Preservation of American Artistic Heritage. It pretty much goes by SPAAH, and I have never been more grateful for the gift of acronyms.

SPAAH has two goals. One is to help re-establish the reputations and legacies of American artists, who have reached a level of achievement but have become forgotten over time. The other is to assist working artists reach their creative goals and build business acumen. With other draws on my time, I have frequently relegated SPAAH to be more of a hobby with most resources going toward the development of its first major publication, the book Martin Barooshian: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Prints, 1948-1970. But we have had other events to celebrate. Plein Air Magazine named Mary Giammarino, an artist SPAAH works with, among 2020’s 11 “artists to collect now”!

I had not intended to write a book. For promotional and informational use by curators and dealers, my SPAAH team and I started to develop a modest 8-page Barooshian primer, a short bio and a few images. A superficial dive into Barooshian’s life suggested a rich story requiring exploration. Trying to select a handful of images revealed a trove of captivating art: paintings, prints, drawings.

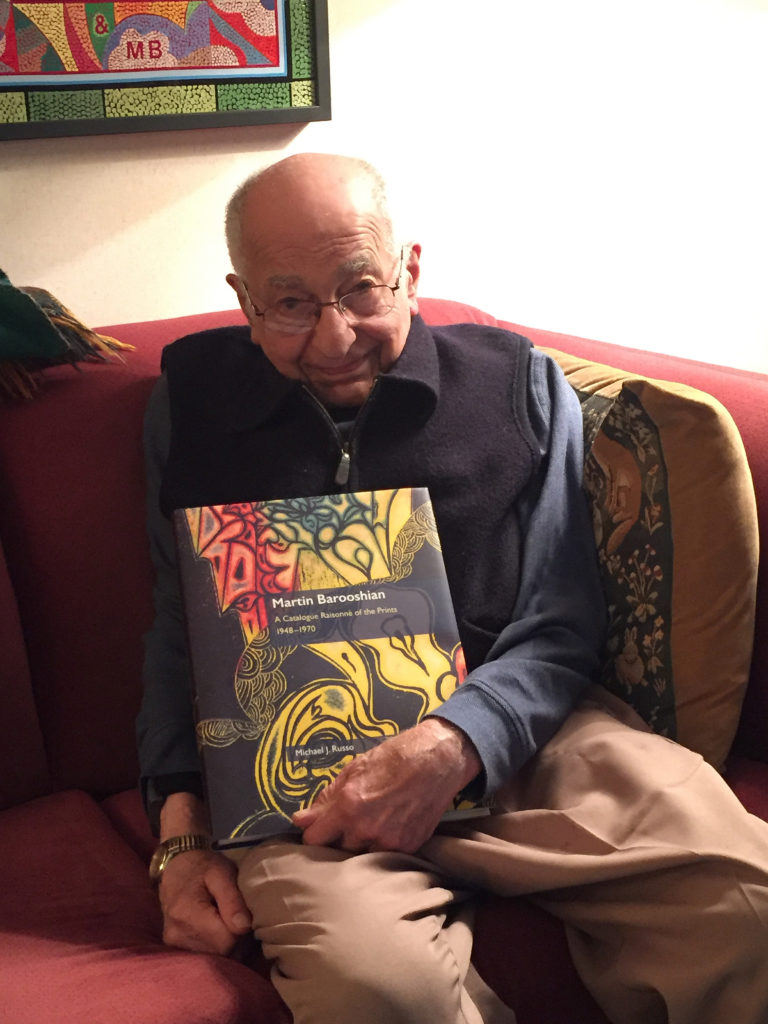

OK, we thought, so maybe we should do a 16-page or 32-page monograph…? Three-hundred pages later, we published a compelling and beautiful coffee-table book that chronicles Barooshian’s life and artistic development and presents a complete catalog of his prints from a 23-year period of his prolific career.

Was He in Prison?

From the start we knew that we wanted to do something different: present the artwork and a biography with minimal interference, allowing readers to learn about Barooshian’s life and witness his artistic development on their own terms. This pathway meant creating a more humanized, personal portrait of the artist — eschewing the academic and critical assessment that is frequently included in similar art monographs.

Of course, writing about a living person I knew well made getting to the final draft even more complicated and surprisingly difficult. My first attempt at telling his story was a tightrope walk, trying to adhere to the goal of keeping it brief while generating interest and smoothing out the rougher edges. Karen was not having any of it.

She saw right through the awkwardness of attempted sensitivity and wondered why I was sucking the life out of a colorful story, speeding along and leaving out the best parts. Some of her comments made me laugh out loud: “What happened here? Was he in prison for a decade?” (Note: He was not.)

Is It OK to Lift the Veil?

Karen was able to transport me into Martin’s world as filtered through the eyes of an interested reader to see what made his experiences so special. She frequently cited instances where I would set up a situation and then not deliver: “Who wouldn’t want to know what it was like to be an artist in postwar Paris?”

She helped me to bring a lightness and a beauty to a lifetime of creative pursuit, doubling the bio in size and allowing the reader to actively participate in his journey. We succeeded only because of Karen’s kind guidance and thoughtfulness, understanding what I needed even before I could articulate it.

I always get slightly saddened every time an appraiser or art expert says, “Not much is known about the artist.” Or worse, they lead with clearly gross speculation. So, from a practical place, I wanted to concentrate our efforts on telling the story only we could tell right here, right now, with direct, even intimate access to the details of Barooshian’s personal and artistic life from the artist himself. Some questions could only be answered by Barooshian, exposing practical reasons for some outcomes and preventing any future speculation.

Q: Out of hundreds of prints, why only one silkscreen? A: As a teen, Barooshian took a job at a commercial silkscreen factory, which he learned to loathe. Q: Why do his paintings of the 1980s take on a lightness and spirituality? A: This was likely a result of his divorce from his first wife. Q: Why is one of his paintings named for the fifteenth-century van Eyck brothers? A: Barooshian solved one of his greatest painting problems by adapting a formula from one of their 500-year-old journals.

What Does It Take to Fill the Gaps?

Our approach to Barooshian’s story is also more in line with the needs and desires of the contemporary art viewer. In the past, the final artistic work produced was paramount. Now, the artist’s identity, motivation, and process are of equal or even sometimes greater importance. We sought to fill in these gaps, providing constructs for how Barooshian’s experiences, including his identity as a child of immigrant Armenian Genocide survivors, shaped and motivated his artistic output.

Above all, we wanted to find the extraordinary hiding among the experiences of an ordinary life. Barooshian’s sheer will and commitment elevate his story as a teacher, husband, parent. He throws himself with joy into the slipstream of art history, continuing to create under the best and worst of circumstances. In this way, his story is transcendent.

Even at 92, with severe physical impairments and isolated because of Covid-19 in an assisted living facility, Barooshian made art every day. He defied his circumstances. He found reason and purpose, as he had for 80 years in the act of creation.

Martin Barooshian passed away peacefully on January 25, 2022, just a few months after the Museum of Fine Arts Boston added 35 pieces — important woodcuts, etchings, lithographs, preparatory drawings, and one monotype — to their collection. The recent rediscovery of Martin’s work has been very exciting, and this honor solidifies his legacy. He fantasized that someday the MFA would have a large collection of his art. He lived to see it happen.