by Greg Dorchak

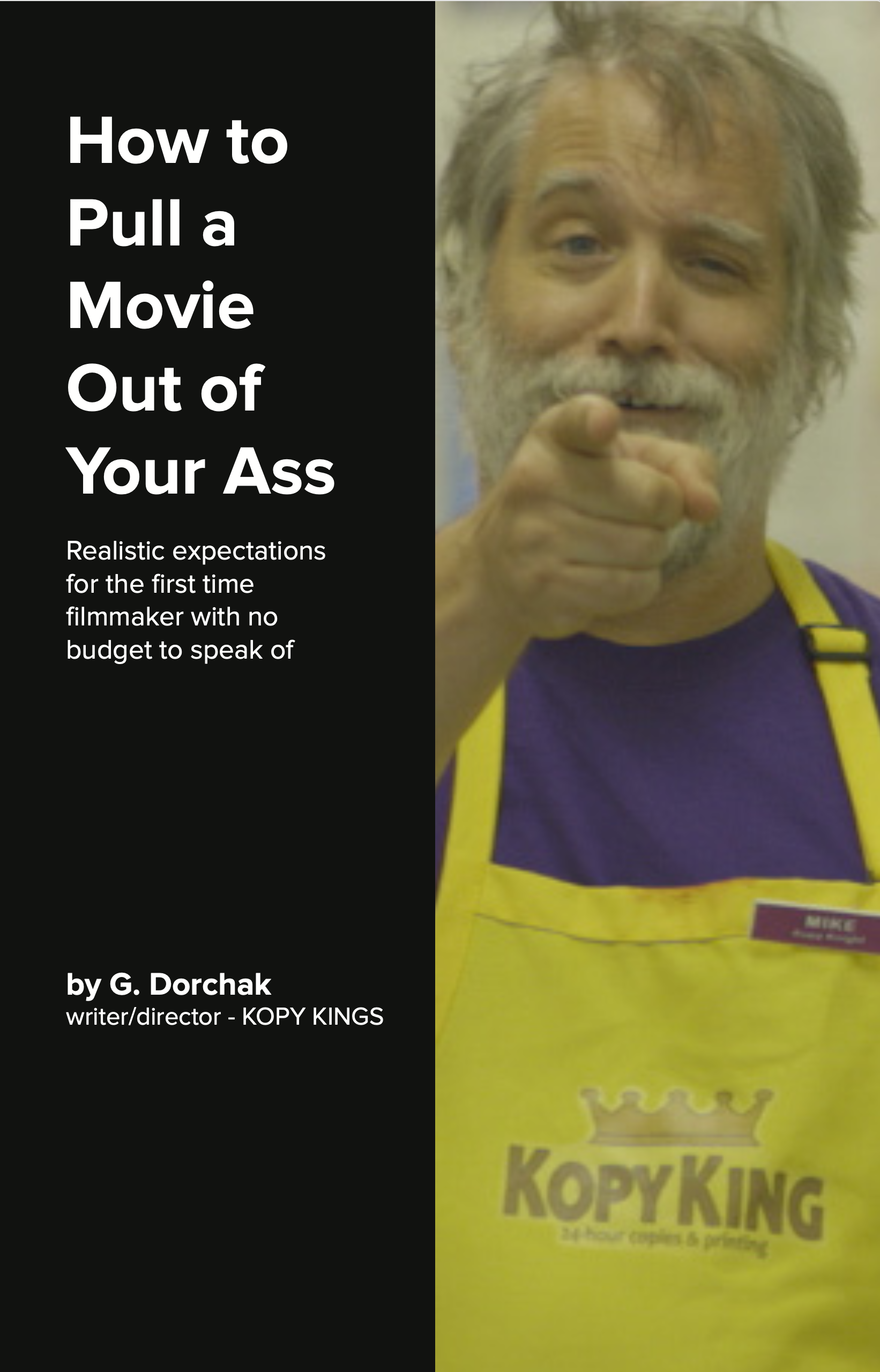

Greg Dorchak is a writer, cartoonist, actor, and filmmaker living in Austin, Texas. He and I along with our families have been friends for more than 25 years. Greg’s acting credits can be found on IMDB, his books are on Amazon. His cartoons pop up here and there, including on my fridge. While I wasn’t his editor, I am delighted to share his feedback on writing a how-to and to help promote his latest book, How to Pull a Movie Out of Your Ass: Realistic expectations for the first time filmmaker with no budget to speak of. And, if you are looking for a good laugh, consider renting his indie film, “Kopy Kings.”

I am a screenwriter. I also write sketches, comic strips, greeting cards and children’s books. I like the short form, get in, tell a story, get out. I have never really wanted to write a novel. It just seemed like so much work, plus most of my stories lend themselves to scripts, not inch-thick how-to books. But a few years ago I felt I had something to say that could not be said in ninety pages, and I felt it needed saying. That’s how writing a how-to happened.

When things crumble or go sour on a film project, especially for a first-timer, it can really – REALLY – be soul-crushing for the filmmaker, many times turning them off for good. I have known a lot of would-be filmies who just quit the business after a traumatic first-run. They felt like everything was stacked against them, and they couldn’t get around the stack. I have been there myself, and I do not dig that feeling.

I had a lot of first-hand experience to draw on for this book, which made writing it an easier experience for me. When starting out, write what you know. Right? So I wrote a how-to book of realistic expectations for the first-time filmmaker.

In 2008, I was working on making my first feature film, to be shot in and around Austin. It did not take long for everything to go down the toilet with the cherry on top when a world financial collapse started at the tail end of September and had us dead in the water seven days into production. Everything that happened felt very personal or at least one of a kind.

Knowing now what you didn’t then

In 2015, I had a chance once again to make a movie. I thought back to things that happened on that first film. A lot of the issues we had were square on my shoulders. Why? For simple lack of experience seasoned with not knowing what I didn’t know. By 2016, we had an actual watch-in-a-movie-theater movie made.

The space between that 2008 project and the 2015 one is what made all the difference.

Understanding the heart of what matters

Many times in those almost eight years I found myself shaking my head and wondering why nobody tells you – in plain language – what to expect as a filmmaker, good or bad. What you typically get with how-to books is a step-by-step procedural on how one specific movie was made, embellished just enough to show the triumph and gloss over the uglier realities. And while I can appreciate why that is, I felt the film industry needed a book that has broader strokes and useable information about the crap that happens pretty frequently on any set, geared specifically to those first-time filmmakers.

I am the type of person who likes to know the industry’s worst-case scenarios. Knowing the kind of crap that happens and when it happens to you. Knowing that it isn’t just you this happens to makes the worst of it easier to take. It’s kind of like having a bad relationship and then listening to the blues and realizing, Yeah, man – this happens to everybody. You can get through this.

Getting a how-to started

Thinking about writing such an in-depth book was pretty daunting. Getting the time to write was a huge obstacle. I was trying to eat an entire turkey dinner in one bite. But then, as happens, a change came along that I would not have thought of. Nobody did. Pandemic lockdown. In the middle of this worldwide event, with all the angst it brought, one thing opened up in a big way: time.

In 2021, I sat down and wrote the book that I wish had existed when I started my first feature: How to Pull a Movie Out of Your Ass. I wrote it as a broad-stroked overview of how a movie is made, what could go wrong and how to work around certain issues. “Realistic expectations” was my battle cry. As examples, I used the first movie that I successfully made in 2015, “Kopy Kings,” to contrast with the first movie I started to make years earlier. The difference between the successful production and the crash-and-burn production, I thought, was a nice illustration.

Getting a how-to finished

Within lockdown I was able to channel the angst of my previous production into reflection. The basic ideas I wanted to put in the book were in my head, so I could focus on those ideas with a clear mind – something I would not have been able to during or just after the failure. Once I sat down to write, I found it easy to arrange the book in a way that felt made sense. With a book of this type, I could jump around as the muse took me, adding information and anecdotal sidebars that did not need linear thought. That giant turkey dinner turned into individual ingredients, sides and main dishes. And what’s more, I actually enjoyed writing; it was a lot of fun recounting the experiences and relating them in an easy-to-read entertaining manner.

It took me about four months to write and then another month to rewrite before I let anyone read my first draft – and that person (perhaps unfortunately for her) happened to be my wife. I wanted someone who had a basic idea about how to make a movie but no specific or nuanced experience making one to see if she thought the material would be helpful. She enjoyed it, told me where it wasn’t working and gave suggestions.

Getting a how-to past a first draft

I sent the next draft to my daughter, who is an editor and a teacher. She cleaned up my ramblings, which ensured the language was plain but informative, worthwhile, and entertaining all without diluting my own voice. Find yourself a great editor. You will not regret it.

The next few people I sent the manuscript to were friends. They all had varying levels of experience in the film industry. I wanted to get their take. And then, after a month or so of focus-group testing, I felt the book was ready. But…ready for what? Did I want to shop it to publishers and hope at some point over the next few years somebody would publish it?

I already had a lot of experience with that sort of thing between children’s books I’d written, cartoons I’d drawn, and a movie I’d tried to get distributed. Getting a book picked up by a publisher can be time-intensive and can be a bit soul-crushing in itself. Rejection letters are no fun at all. I had to think about what my goals were and what the realistic expectations were.

Getting a how-to published

I had self-published my children’s books and self-distributed my movie. So, I opted to self-publish again, which makes a how-to available to the public pretty quickly. One of the easiest ways to get self-published is through Amazon. Being a graphic artist and having spent a lot of time in publishing, I could easily create the digital files myself. The account setup to final push of the publish button happened quickly and at a cost of $0. If you’re someone who does not have that graphic artist ability, plan on spending some money to get someone else to create your files.

Years ago you paid publishing companies called vanity presses to create your book. You had to buy a dozen or so cases of books up front and figure out how to sell those. Or, you had to go through the heartbreak of tossing three hundred pounds of books in the dumpster. Today’s POD (print on demand) system is awesome. Create a book. Upload the files. And, when someone wants one, it gets printed right then and drop-shipped. No stock sits around prepaid and unused.

As the writer, you can buy “author’s copies” at a great discount to do with as you wish. You also retain all rights. Fantastic system for the new writer who wants to publish immediately to jumpstart their career. After that, you can always move to a more traditional publisher if the opportunity arises.

Getting a how-to sold

As awesome as this system is, keep in mind that the biggest issue with self-publishing is that the onus of marketing and selling is completely on you, the writer. A lot creative types, myself included, can create all day. But, put a business plan in front of them and they freeze. If you have marketing and PR savvy, good for you. You are miles ahead in the game. If not, be prepared to learn quickly.

You have a lot of ways to advertise nowadays. But, if you don’t know how to do them correctly, they might as well not exist. Social media, ads in trade publications, hitting up booksellers directly, getting into book fairs all take a lot of time and energy…or money. Either you will spend the time and energy (and most likely money) doing the work that needs to be done, or you will spend the money on someone who knows how to do what needs to be done. Finding that person can be very trial and error-y.

I myself have never mastered the marketing aspect. The correct equation eludes me, and all the how-to and self-help books out there on how to “absolutely sell 50,000 books” may not absolutely resonate with me or my particular personality or my set of skills. Or my bank account.

Revisiting what went wrong without judgment

Probably the best thing I can advise you to do early on as a writer is to figure out what sort of writer you are. Set a definite goal. What does success look like to you? Having my books on some media outlet’s bestseller list isn’t extremely important to me. I write because I feel I have something to say, and I want to quickly see that idea get out there among the people. I can handle my own postings on social media and get a handful of bookstores to sell on consignment. My children’s books I send to friends having kids. They do some word of mouth. My filmmaking book I contact local bookstores, university bookstores, film festivals, and social media and industry chatroom posts.

Most creative types ain’t in it for the money, and I am no different. Would I love to have my books available on a much larger scale? Hell yass. However, am I also happy if my filmmaking book helps even one person keep it together enough to make a movie or two without becoming completely soul-crushed? Hell yass. Or, if a friend texts me a picture of their two-year-old reading their favorite book, and it is one of mine? Hell yass. I consider these successes.